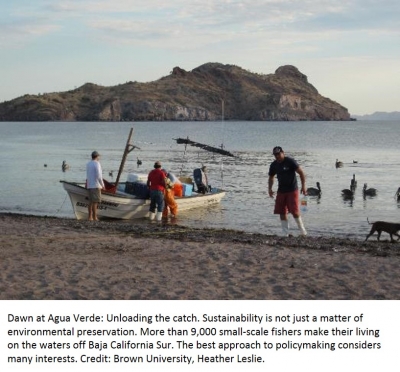

The waters of Baja California Sur are both ecosystems and fisheries where human needs meet nature. In a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers assessed the capacity to achieve sustainability by applying a framework that accounts for both ecological and human dimensions of environmental stewardship.

PORT ARANSAS, TX – In 2009, the year she won the Nobel Prize for economics, Elinor Ostrom proposed a framework to integrate both the institutional and ecological dimensions of a pervasive global challenge: achieving sustainability. Now researchers have put Ostrom’s theory into practice in the Mexican state of Baja California Sur. The result is a one-of-a-kind map of regional strengths and weaknesses that can help guide fishers, conservationists, and other decision makers as they consider steps to preserve the peninsula’s vital coastal marine ecosystems.

Those ecosystems are vital to sustaining fisheries that provide food and income. The value of Ostrom’s framework is that it encourages researchers to consider both natural and human values, said lead author Heather Leslie, the Peggy and Henry D. Sharpe Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Biology at Brown University.

“By taking a multi-disciplinary approach, we were able to complete a comprehensive analysis that integrated a variety of data related to coupled human-natural systems.” said Erisman, co-author of the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and Assistant Professor of Fisheries Ecology at the University of Texas at Austin Marine Science Institute. “This strategy produced insightful results that would not be visible had we focused only on a single discipline such as ecology or economics.”

Leslie, Erisman, and their colleagues — anthropologists, economists, ecologists, fisheries scientists, geographers, and other social scientists — gathered data on 13 social and ecological variables for each of 12 regions around Baja California Sur. They developed a profile of sustainability potential for each region along the four dimensions laid out in Ostrom’s framework: governance systems and actors (the social) and resource units and resource systems (the ecological). What became clear is that each region’s profile is quite different, suggesting that the most effective policies for achieving sustainability will be ones tailored to shore up each area’s weaknesses without undermining its strengths, the authors wrote.

Magdalena Bay and Todos Santos

Take, for example, stories about the Pacific coast regions of Magdalena Bay and Todos Santos, illustrated by the researchers’ maps. If Baja California Sur is a leg, then Magdalena Bay is the knee and Todos Santos is the front of the ankle.

In Magdalena Bay, fisheries are diverse and productive. But the area is also crowded with fishers who use many different kinds of gear and do not necessarily follow the same locally developed rules, Leslie said. While the ecological foundation for sustainability looks good there, the social dimensions are considerably less promising.

In Magdalena Bay, fisheries are diverse and productive. But the area is also crowded with fishers who use many different kinds of gear and do not necessarily follow the same locally developed rules, Leslie said. While the ecological foundation for sustainability looks good there, the social dimensions are considerably less promising.

“Depending on which type of data one musters regarding the potential for sustainable fisheries, Magdalena Bay could be scored as either well-endowed or quite weak,” wrote the research team, which also included co-authors Xavier Basurto of Duke University and Octavio Aburto-Oropeza of the University of California–San Diego.

Meanwhile in Todos Santos, local fishery management institutions are quite strong. There is considerable cooperation and compliance among fishers, based on the social science surveys the authors conducted, but the nearshore ocean is less productive and yields fewer species than Magdalena Bay, just 150 miles north. The team’s work reveals that, while they are not far apart geographically, the regions are polar opposites in their social and ecological profiles.

The researchers suggest that in Magdalena Bay, the most productive strategy might be to cultivate stronger local institutions, but in Todos Santos, maintaining local institutional strength and bolstering capacity in the water might make more sense. They caution however that in most cases, people have considerably less influence over ecosystem dynamics than themselves.

Are there fundamental trade-offs?

The fine-grained diversity of regional strengths and weaknesses apparent in the maps is borne out statistically. The researchers looked for correlations among the four dimensions across Baja California Sur and found few.

The rarity of reliable relationships between strength in one dimension and strength in another was a surprise. It’s a result that merits more scrutiny, Leslie said, because while it could reveal a shortcoming of the analysis — this is among the first attempts to apply the social and ecological framework in a comparative, quantitative manner it might instead reveal something more insidious: a fundamental difficulty for regions to be strong across the board.

“Does something like this represent fundamental trade-offs?” the researchers asked. “What we found suggests that. There is no place that does well in every dimension.”

The paper’s authors are Heather Leslie, Mateja Nenadovic, Leila Sievanen, Kyle C. Cavanaugh, Juan José Cota-Nieto, Brad Erisman, Elena Finkbeiner, Gustavo Hinojosa-Arango, Marcia Moreno-Báez, Sriniketh Nagavarapu, Sheila M. W. Reddy, Alexandra Sánchez-Rodríguez, Katherine Siegel, José Juan Ulibarria-Valenzuela, and Amy Hudson Weaver.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (grant: GEO 1114964), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Brown University’s Environmental Change Initiative and Voss Environmental Fellowship Program, the Walton Family Foundation, and the World Wildlife Fund Fuller Fellowship Program supported the research.

Press release courtesy of Brown University, David Orenstein 401-863-1862.