Did you know that Caribbean parrotfishes and surgeonfishes eat poop? A study released this week in Coral Reefs is the first to document and explain what may be driving this behavior. These abundant fishes are best known for the important role they play on coral reefs by eating algae that can otherwise overgrow corals. While algae are rich in carbohydrates, they can be low in protein and some essential micronutrients. The researchers found that compared to an algae-based diet these feces may be a rich nutrient supplement–a fish "vitamin sea."

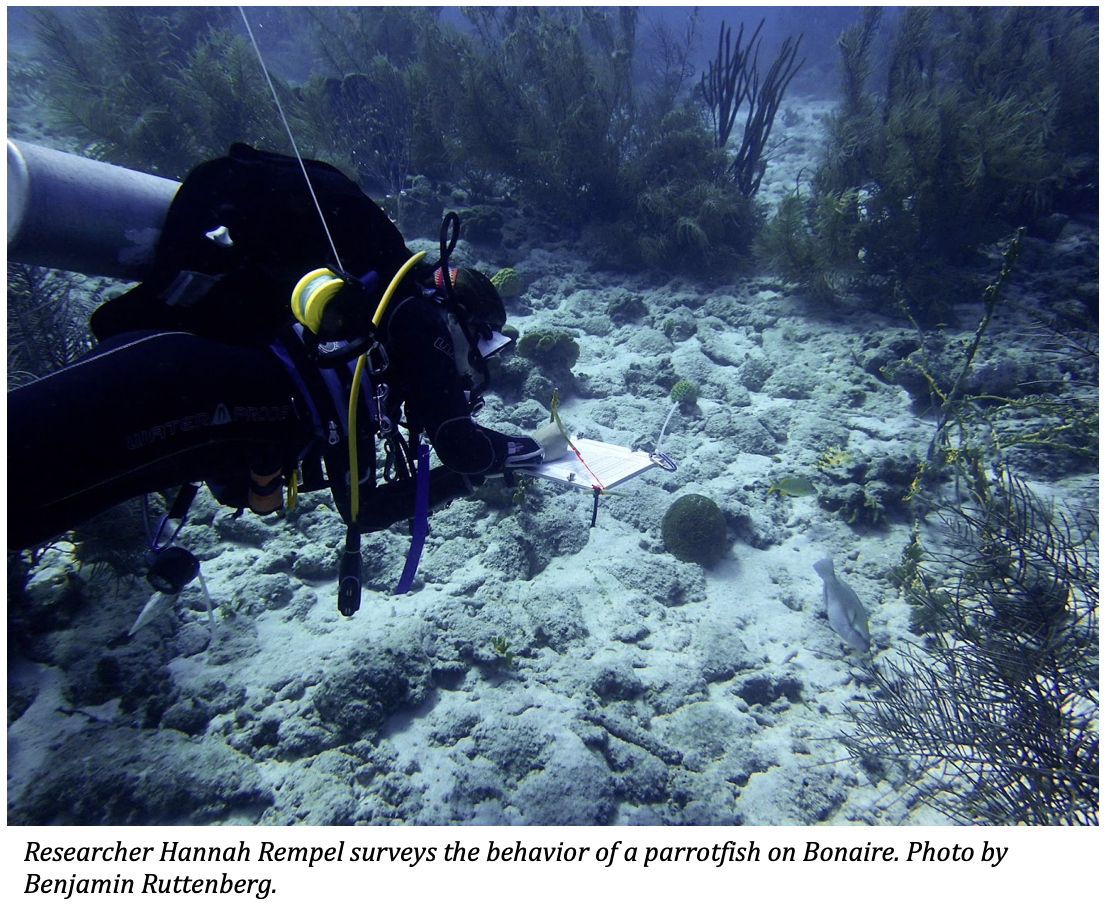

In a study co-led by Hannah Rempel, a Ph.D. student at The University of Texas Marine Science Institute, and Abigail Siebert, a former undergraduate student at California Polytechnic State University, the researchers found that the feces of a common plankton-eating fish are an important, yet previously unknown source of food for herbivorous coral reef fishes.

In a study co-led by Hannah Rempel, a Ph.D. student at The University of Texas Marine Science Institute, and Abigail Siebert, a former undergraduate student at California Polytechnic State University, the researchers found that the feces of a common plankton-eating fish are an important, yet previously unknown source of food for herbivorous coral reef fishes.

The researchers found that 85% of the poop pellets from a plankton-eating fish get eaten by other coral reef fish. “What was striking was to learn was that of those feces consumed by fish, over 90% of them were consumed by parrotfishes and surgeonfishes alone,” said co-lead author Rempel. Parrotfishes and surgeonfishes are the dominant consumers of algae on Caribbean coral reefs. However, algae are typically a low-quality nutritional resource. “Compared to algae, these fecal pellets are rich in a number of important micronutrients. Our findings suggest they may be an important nutritional supplement in the diets of these fishes.”, said Rempel. This study is the first to document feces consumption by herbivorous fishes in the Caribbean and highlights this important, but understudied food resource of feces.

Coral reefs are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, but they are also relatively low in nutrients. Recycling of nutrients is essential to support such a high abundance and diversity of organisms. This study highlights the importance of fish feces in nutrient recycling on coral reefs, particularly for these important herbivores.

Rempel and Siebert are joined in the study by co-authors Jacey Van Wert with the University of California Santa Barbara, Kelly Bodwin with California Polytechnic State University, and Benjamin Ruttenberg with California Polytechnic State University. The research was supported by the California Polytechnic State University Baker/Koob Endowment Award, Bill & Linda Frost Fund, Dr. Earl H. Myers & Ethel M. Myers Oceanographic & Marine Biology Trust, Harvard Travellers Club Permanent Fund, and the American Museum of Natural History Lerner-Gray Memorial Fund.