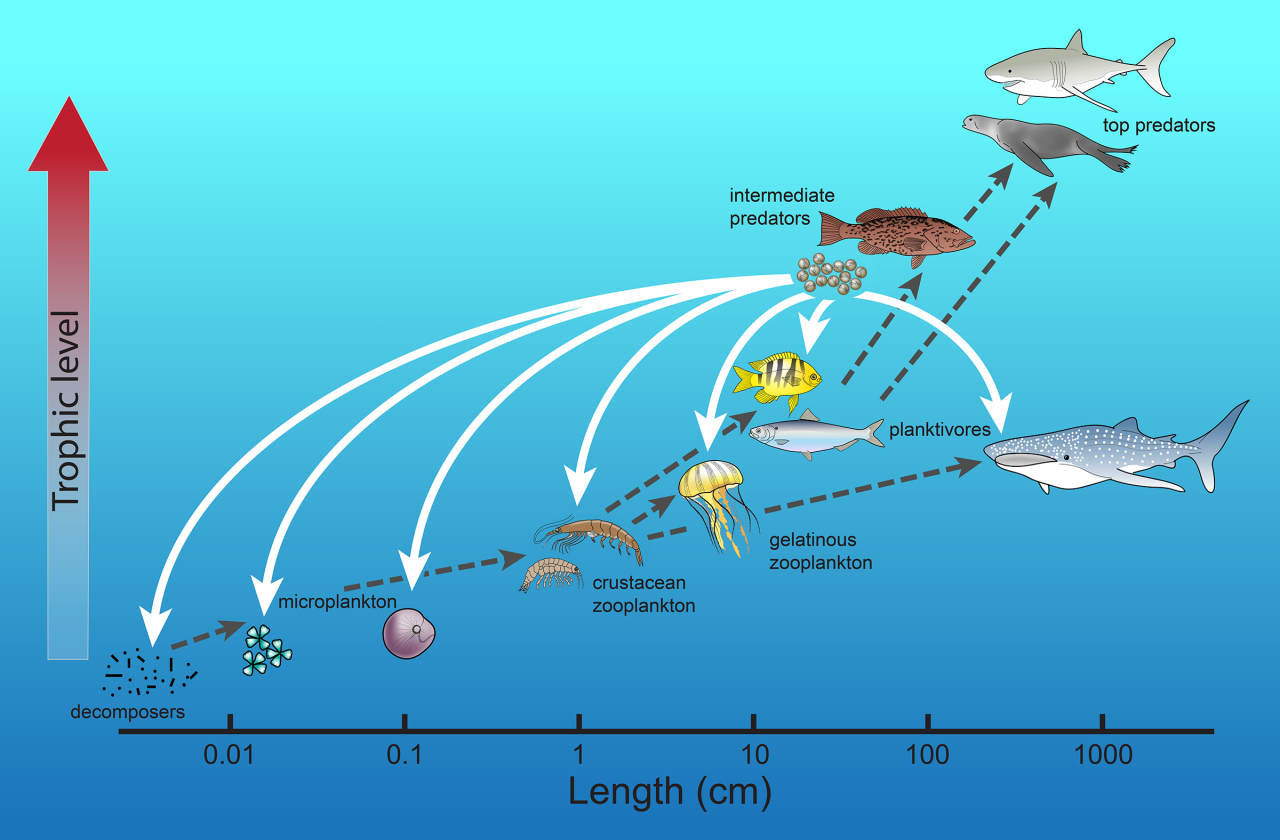

PORT ARANSAS, TX - Do you remember in fifth grade science class learning about food webs? Plants absorb energy from the sun, plants are eaten by animals, and smaller animals are eaten by bigger animals. Generally speaking, the flow is from smaller to larger organisms. An analysis by researchers at The University of Texas Marine Science Institute and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute reveals how the flow of nutrients in the ocean can also go in reverse, from larger animals to smaller ones. This new understanding has implications for conservation and fisheries management.

Here's how the reverse food web works: marine animals release extremely large numbers of eggs when they spawn. Organisms from microscopic plankton to the largest fish in the ocean consume most of these eggs. Many of the egg consumers are smaller than the animals that released the eggs, representing a reversal of the food web.

While egg munching might only supply a small portion of a consumer's energy needs, the eggs contain essential fatty acids, molecules especially important for the health of almost all animals and for the health of whole ecosystems. The researchers, led by Lee Fuiman, demonstrated that the eggs of marine animals have very high concentrations of these fatty acids – tens to hundreds of times more than animals their size.

Many fish populations produce trillions of eggs each year. Many species form huge spawning aggregations to coordinate the timing and location of their spawning. This results in an “egg boon” – an immense but temporary concentration of highly nutritious fatty acids.

The research also demonstrates hidden impacts of human activities. For example, commercial harvest of large fish that produce millions of eggs can remove tons of fatty acids from an ecosystem, which can have cascading effects on those biological communities. This new understanding of aquatic food webs could help improve management of marine resources.

The reason concentrations of essential fatty acids are so high in fish eggs is that the embryos that develop from them require the fatty acids for their development, growth, and survival. The same is true for humans, which is why essential fatty acids are commonly found in prenatal vitamins.

Beyond their value to individual organisms, egg boons are important to ecosystems. This research reveals linkages between animals and environments that have important implications for understanding how food webs change over time and how they vary from place to place. Through egg boons, fatty acids produced on coral reefs are carried offshore by currents, and fatty acids produced in the sea feed animals in rivers and on land when fish such as salmon migrate to freshwater to spawn.

The researchers’ novel work will soon be published in the prestigious journal Ecology.