In the oceans lurks a stubborn pool of dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) that no one had a clue how it formed – until now. A recent study in the Geophysical Research Letters provides the first discovery of how and why this refractory, virtually unusable, nitrogen pool is formed. Like the refractory pool of carbon, dissolved organic nitrogen, while smaller at about 100 gig tons, has significant implications for how global nitrogen cycling in the ocean can change with changing climate. The nitrogen in the refractory dissolved nitrogen pool can be as old as 4,000-6,000 years, and if there are changes to that pool that return the nitrogen to ammonia, it could cause large-scale algal blooms and eutrophication.

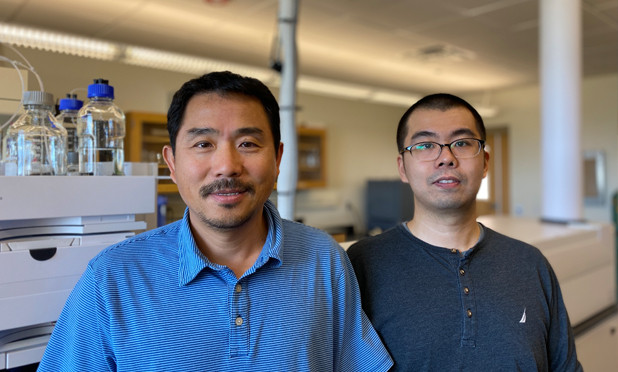

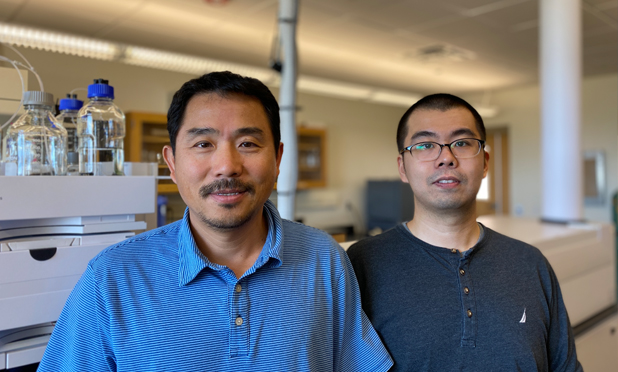

In the recent study led by Drs. Kaijun Lu and Zhanfei Liu, both from The University of Texas Marine Science Institute, the first evidence that the type of amino acid decomposed by microbes determines what gets converted to refractory, or unusable, dissolved organic nitrogen. “It’s a question that has been puzzling people for a long time - there are lots of DON in the deep ocean, but we didn’t know the structure or how or where it came from,” said Dr. Kaijun Lu, Postdoctoral Fellow. Using high-resolution mass spectrometry and stable isotope labeling, the researchers could trace every step of the molecular transformation of three different amino acids (phenylalanine, alanine, valine) from the beginning of when bacteria consumed them to their final products. What the researchers found surprising was that the three amino acids produced different results. More refractory organic nitrogen was formed from Valine and Phenylalanine than from Alanine. These amino acids are the bases of algae in the ocean, and the finding means that the refractory dissolved organic nitrogen pool has more to do with certain types of amino acids than others.

The discovery was long in the making because its challenging to trace the decomposition pathways of nitrogen. It’s easier to trace dissolved organic carbon pathways because you can get rid of the carbon with acid, but it’s still in the system when you do that with nitrogen. “That’s where the beauty of using 15N isotopes kicks in.” “We did an incubation with 14N and 15N in parallel to compare and allow us to pick the exact molecule with the 15N label,” said co-author Dr. Zhanfei Liu, Associate Professor. That method, combined with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry that can measure down to the molecular level, allowed them to describe the molecules with confidence.

This research is the first evidence of how and why the refractory dissolved nitrogen pool forms. These critical insights further detail why certain particular structures may resist decomposition and how dynamic the dissolved organic nitrogen community is.

Drs. Zhanfei Liu and Kajun Lu publish the first-ever descriptive evidence of how refractory dissolved organic nitrogen forms.